The first person who taught me something about death and defiance was the mother of a family friend, an older woman who had moved from Punjab to the United States to be closer to her son. I remember her as delicate and draped always in pastel salwar kameezes. After she was diagnosed with breast cancer, which moved quickly to claim her bones and her brain, her desire to return to Punjab intensified. When my parents told me about the end of her life, it was with a mixture of disbelief and conviction: She survived the days-long journey to the village where she’d been born—laboring to breathe for nearly the entire flight, grimacing through prayers when she ran out of pain medication—and died two days after she arrived.

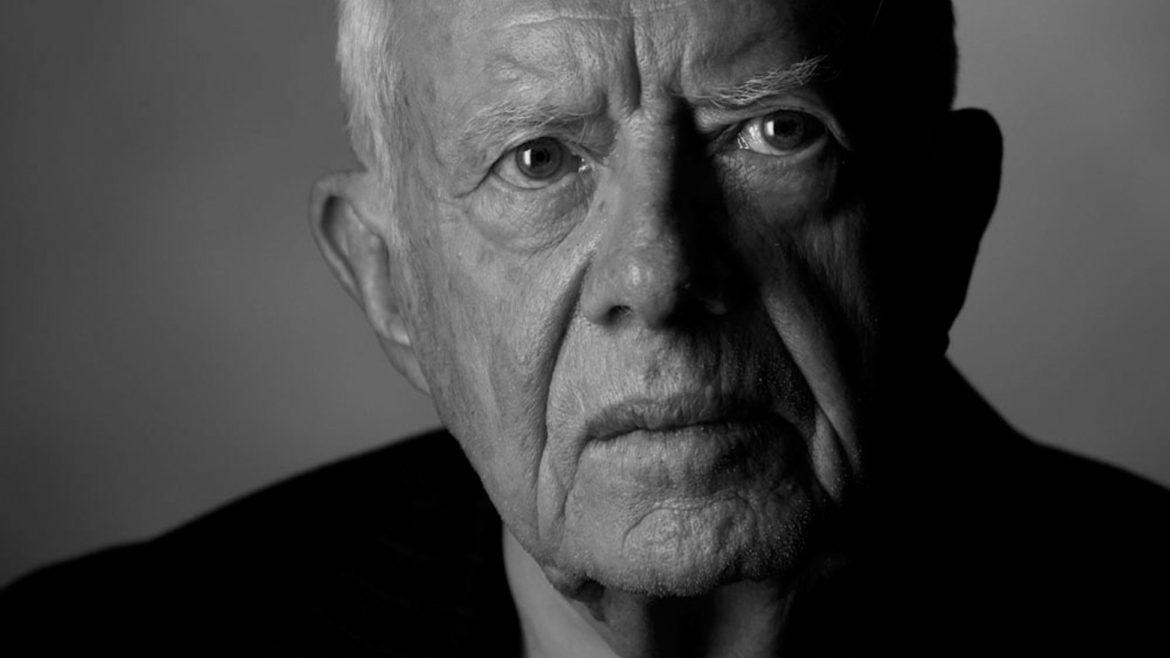

I thought of her story this week as I read about former President Jimmy Carter’s intention to live long enough to vote for Kamala Harris. Carter, who has been on hospice for well over a year, turned 100 on Tuesday and has survived far longer than many expected he would. The notion that he has rallied in order to contribute in one final way to American democracy raises a familiar question that arises in my own work with patients and families: Do we have some control, conscious or not, over when we die? Can a person stretch the days of their life to include a last meaningful act or moment?

As a palliative-care physician, I have encountered the phenomenon of people dying only after specific circumstances materialize. There was the gentleman whose family held vigil in the intensive-care unit while he continued on, improbably, even without the support of the ventilator, dying only after his estranged son had arrived. There was the woman whose fragility precluded any further chemotherapy, but who survived long enough without it to witness the birth of her first grandchild. There was the woman who was deeply protective of her daughter, and died from cirrhosis only after she’d left for the night, possibly to spare her the agony of witnessing her death. The unexpected happens frequently enough that I tell patients and families that two timelines shape the moment of death: the timeline of the body, governed by the more predictable laws of physiology, and that of the soul, which may determine the moment of death in a way that defies medical understanding and human expectations. When people wonder about the circumstance of the last heartbeat, of the final breath, I can see how they never stop searching for their loved ones’ personhood or intention, a last gesture that reveals or solidifies who that person is.

Despite the prevalence of stories suggesting that people may have the ability to time their death, no scientific evidence supports this observation. Decades ago, several studies documented a dip in deaths just before Jewish holidays, with a corresponding rise immediately afterward, suggesting that perhaps people could choose to die after one final holiday celebration. A larger study later found that certain holidays (Christmas and Thanksgiving, in this case) and personally meaningful days (birthdays) had no significant effect on patterns of dying. But this phenomenon doesn’t lend itself easily to statistical analysis, either: The importance of holidays, for instance, can’t quite stand in for the very individual motivations that define the anecdotes shared in hospital break rooms or around a dinner table. And the human truth that many recognize in these stories raises the question of whether we believe them any less fully in the absence of proof.

Palliative care often involves helping people confront and develop a relationship to uncertainty, which governs so much of the experience of illness. And when my patients tell me about themselves and about who they are now that they are sick, willpower often makes an appearance. Many say that if they focus on the positive, or visualize the disappearance of their cancer, or fight hard enough, they will win the battle for more time. I hear in their words echoes of what Nietzsche wrote, what the psychiatrist Viktor Frankl used to make sense of his years in German concentration camps: “He who has a why to live for can bear almost any how.”

And we want to believe that love or desire or commitment or heroism is still possible right up until the very end. As my patients grow sicker, and as death approaches, I talk with them and their families about what they can hope for even if a cure isn’t possible. That, in fact, death can still contain something generative. A time that may have seemed beyond further meaning becomes instead an opportunity, or an extension of the dying person’s commitments to their country, their family, their dreams. Soon, President Carter will be able to cast that vote: Next week, Georgia registrars will start mailing out absentee ballots; early voting begins the week after that. His promise to himself is a reminder that dying cannot fully dampen purpose, even as a person’s life narrows.

The idea that willpower can be an ally against death is appealing too, because it offers the possibility of transcendence, of defying the limits that the body, or illness, may impose. But, having also seen the many ways that the body does not bend to the mind, I do find myself regarding willpower with caution: What if you as a person are a fighter, but your body simply cannot fight the cancer any longer? I wonder, with my patients, if they can strive for more time without shouldering personal responsibility for the limits of biology. Similarly, two people on ventilators may love their families equally. One may die only after the final beloved family member arrives, whereas the other may die before the person rushing across the ocean makes it home. We don’t always know why. If Carter casts his vote and dies shortly thereafter, that might affirm the notion that others, too, can write the final sentence in their story. But what would it mean if Carter died before casting his vote? If he lived another year, or if he lived to see Donald Trump take office again, or watch the election be violently contested? Living with loss requires remembering that we can locate the person we have loved or admired in any given set of events that comprised their life, not just the last one.

I try to imagine my family friend’s long flight from Los Angeles to Delhi, and her ride in the taxi back to Punjab. I think about how she found a way to endure what she was told she couldn’t, all to feel beneath her feet the soil she knew best, to die in the one place that she felt belonged to her. What if her doctors had been right and she had died on the plane? My family might have mourned her single-mindedness, or we might have admired her defiance nonetheless. What makes these stories so compelling is that they remind us that death, however ravenous, cannot devour hope or possibility, even if what transpires is not the ending we imagined.